Skeletons of Summer: What Dead Plants Leave Behind

Explore the hidden architecture and quiet beauty of dried plants, seed pods, and tree rings, nature's designs revealed as summer fades to autumn.

The garden sounds different now.

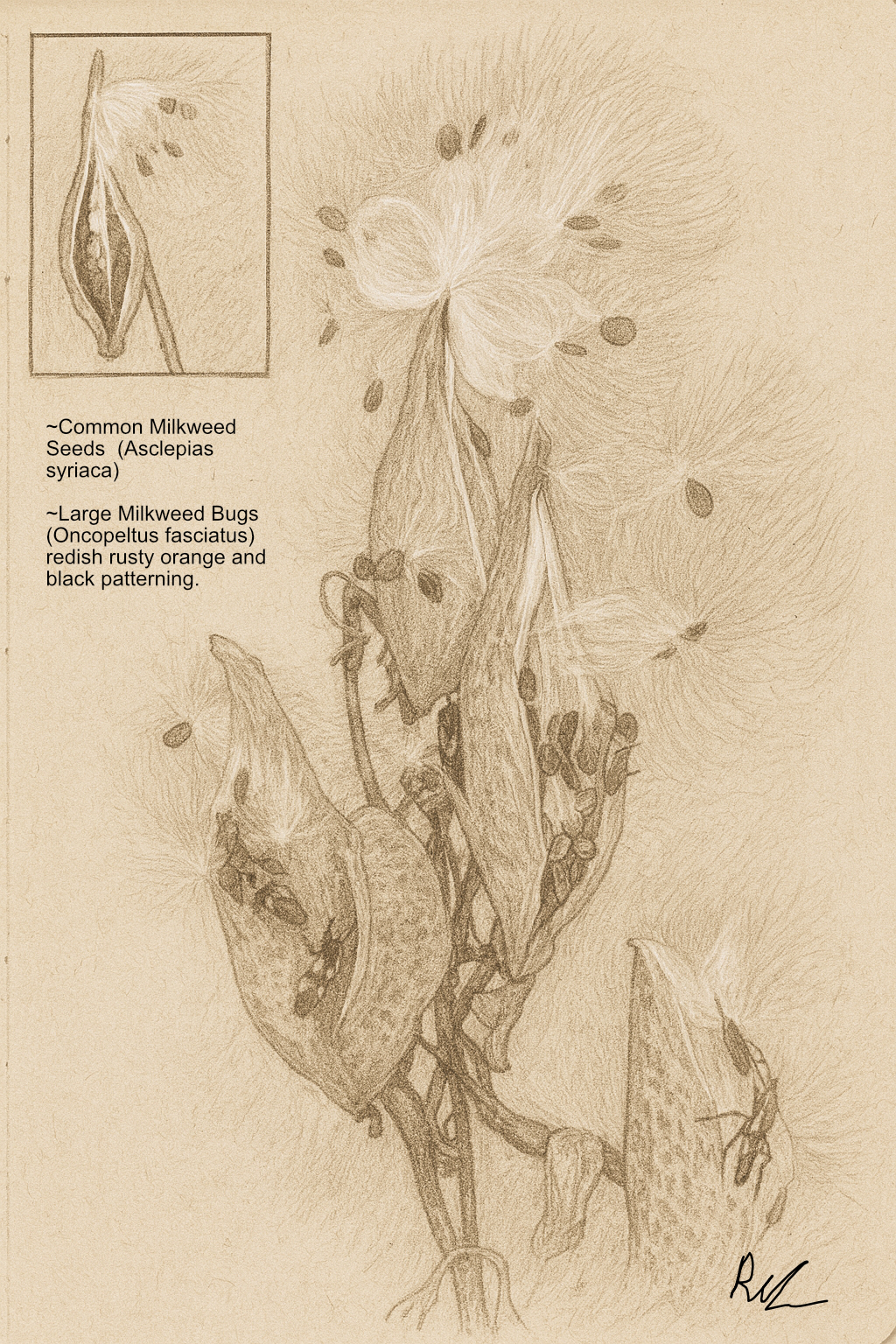

Where bees once hummed and leaves whispered against one another, the air has turned dry and still. Grass blades stand rigid in the wind. Seed pods crack open along invisible seams. I brushed past a stalk and watched a hundred silken seeds drift skyward like a sigh, a subtle reminder that even in passing, plants are architects of tomorrow’s wildness. Touch the rough rib of a poppy pod, or run a finger along last year’s tree ring, that groove was a dry summer, that swelling a season of rain. In these remnants, sunlight and storm are written, awaiting eyes that linger

Listening, I notice that even in stillness, the architecture around me speaks, hinges, seams, levers, sails waiting for the next breeze. The green is fading, but the design remains.

Structures That Stay

Summer’s brightness softens into tans and rusts. What remains isn’t only a shadow of what once was, but the final act of an ongoing choreography. Dry stalks, twisted tendrils, and open pods are doing their last job before frost arrives.

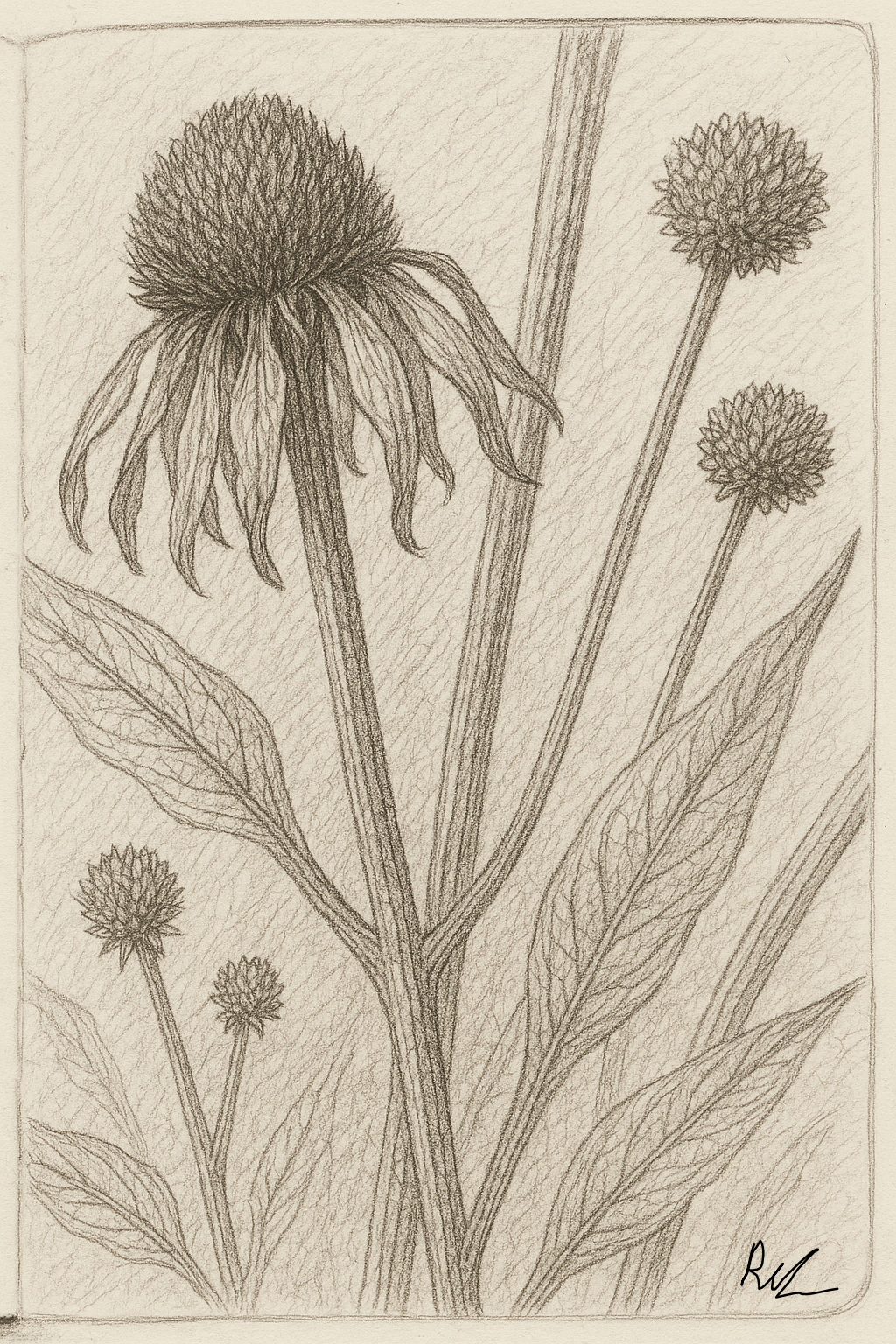

These skeletal remains are built to last, a quiet triumph of plant engineering. Lignin, a tough, intricate molecule woven through their cell walls, acts like an internal armor, giving plants their rigidity and helping slow decay, especially in dry or cold climates (Raven, Evert & Eichhorn, Biology of Plants). When I see last year’s coneflower stalks still standing tall along my path, I am reminded that their resistance to time and weather depends on this invisible strength.

Vascular tissues, the veins in a leaf, the sturdy central stalks, once ferried sugars, minerals, and water. Now, they shift roles, scaffolding seed release, catching snow, or housing overwintering insects. One winter, peeling back the stem of a dead milkweed, I found a ladybug tucked perfectly within, shielded from the cold by the plant’s spent architecture. Moments like this reveal how even in death, these structures become lifelines for the living.

Each dried curve, frayed edge, and fibrous split is a living diagram, a visible record of how a plant grew, the storms it weathered, and the preparations it made for both survival and departure. Holding a dried pod up to the light, scars and curves echo the history of a whole season.

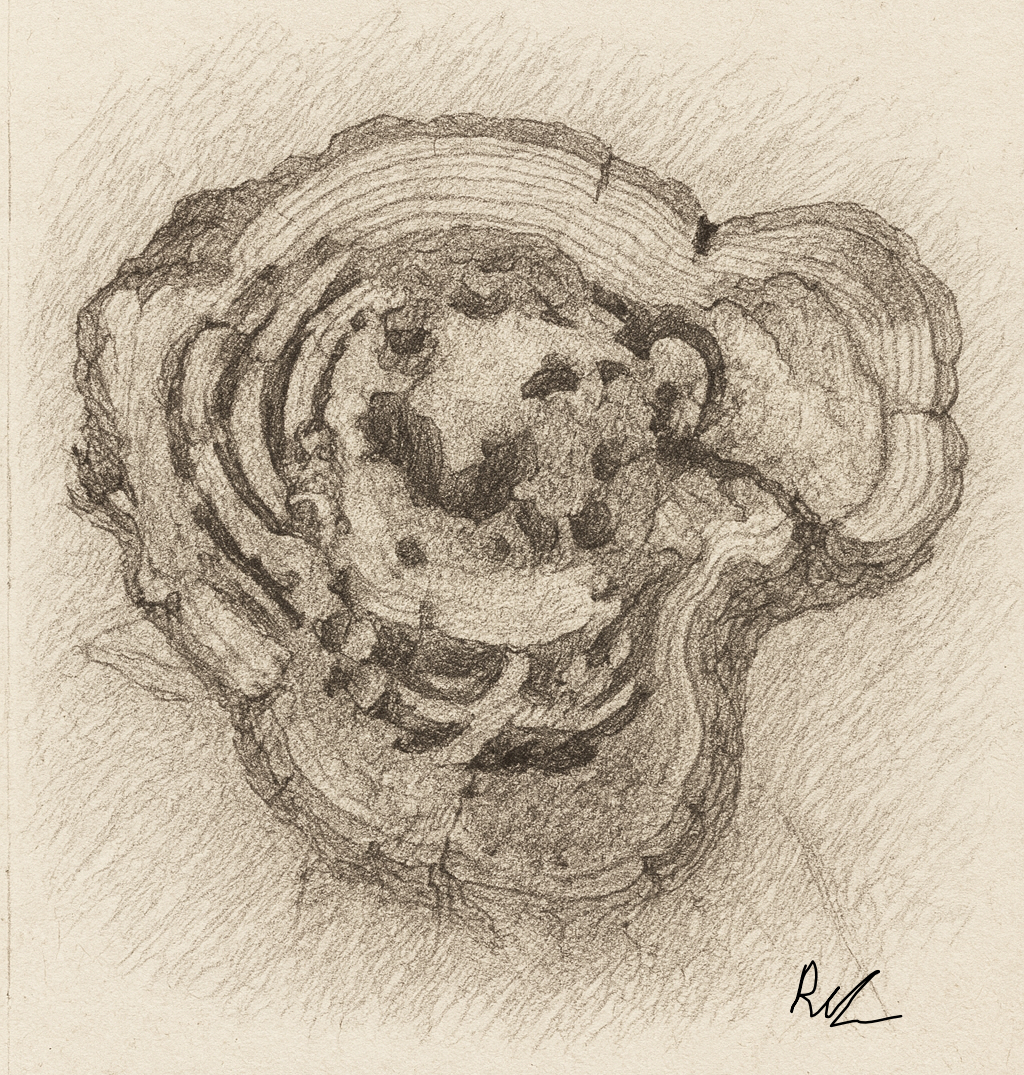

A Record in Rings

Slip beneath the bark to another layer of memory, the rings in a tree’s trunk. Some skeletal remains persist as monuments to time, others as living journals. Years ago, after a windstorm toppled a neighbor’s maple, we traced the story in its cross-section. Broad, pale rings spoke of rainy, generous years, while dark, crowded bands signaled droughts or difficult seasons. Touching a black scar, we imagined the lightning that left its lasting mark.

Tree rings aren’t just private diaries. Dendrochronologists can match these patterns across entire forests, tracing shared events like drought, fire, or even ancient human land use (Fritts, Tree Rings and Climate). These invisible archives turn a fallen trunk into history inscribed in wood, connecting my backyard to global cycles of stress, recovery, and change.

Every ring is a response, a memory of storms endured and sunlight welcomed. Looking closely at enduring wood, I see storytelling at the cellular level, a chronicle not only of the tree’s journey, but of the world it inhabited.

Seeds, Spores, and Silent Motion

Settle in a fall meadow and notice, nothing is ever truly still. Pods twist and pop, powered by a phenomenon known as hygroscopic movement, where plant tissues stretch or shrink in response to shifts in humidity (Glover, Understanding Flowers and Flowering). On a walk through dry grass, I have felt seeds burst at my touch, a gentle rush against my coat, it is like walking through a living choreography, the end of a plant’s quiet rehearsal for dispersal.

These strategies are planned well in advance. As the season wanes, seeds and spores head out into the world. Even as stems and husks break down, they support the wider ecosystem by providing insulation for insects, food for birds, and organic matter that will nourish new life (see Fenner & Thompson, The Ecology of Seeds). A fallen sunflower in my garden was picked clean by a flock of chickadees one winter morning, its empty shell left to mulch into the soil.

Pinecones exemplify another clever strategy: they open and close in response to shifts in atmospheric moisture. On dry days, woody scales bend outward to let seeds drop and catch the wind; with rain, the cone snaps shut, sheltering its contents until conditions are right again. Ferns and mosses employ similar physics but on a smaller, subtler scale. The capsules of mosses (sporangia) release spores only when dried out or jostled by raindrops, a strategy honed through millions of years of evolution.

These mechanisms aren’t accidental or wasteful: each is a product of natural selection. Seeds and spores disperse with precision, increasing their chances of finding the right place to germinate, while the leftover structures continue to serve the broader ecosystem, offering shelter, food, or mulch.

Design in Decay

Some patterns only appear as green gives way to gold. Milkweed pods split with sculptural grace, silk parachutes spaced for flight. A sunflower’s spiraled disk follows mathematical rules, packing seeds for the best use of faint autumn light. I often collect these remnants for my windowsill, marveling at how their lines still hold structure and hope (Raven, Evert & Eichhorn).

Even as husks fall apart, their work is not finished. Petals and hulls shelter next year’s insects and enrich the soil. In my own garden, what looks like decay is really the start of transformation, a lattice of tomatillo, the feathered remains of thistle, all busy repurposing themselves for what’s next.

Not all beauty lies in blooming. Many of the plant world’s most astonishing designs, a willow’s spiraling seed, a cloudburst of orchid pollen, are revealed only as growth gives way to rest and the hush of autumn deepens.

✏️ Your Turn

Go looking for remnants. Find a husk, a pod, a collapsing stem. Sketch it, or simply hold it for a moment. Every fragment you find, each hinge, seam, or sail holds a story of what came before and a hint of what is still to come. In my experience, slowing down to observe with care makes every passing season feel fuller, more connected. Each year, the record of sunlight, wind, and time reveals itself steadily from cell to cell.

To guide your noticing, download the free Sketch Prompt Sheet at rosaliesinclair.com/support. It is designed to help you slow down and notice what is quietly unfolding. By approaching ordinary remnants through both observation and curiosity, you are joining the work of plants, translating the ordinary into meaning, season after season.

[Download the Sketch Prompt Sheet]

Remember, the architecture of death is alive with stories, from seasons past to lives sustained, and silent transformations just beneath your feet

Plant Structure, Lignin, and Decay

- Raven, P.H., Evert, R.F., & Eichhorn, S.E. (2023). Biology of Plants (9th Edition). W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Taiz, L., Zeiger, E., Møller, I. M., & Murphy, A. (2015). Plant Physiology and Development (6th Edition). Sinauer Associates.

- Boerjan, W., Ralph, J., & Baucher, M. (2003). Lignin Biosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 54, 519–546. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938

Tree Rings and Dendrochronology

- Fritts, H.C. (1976). Tree Rings and Climate. Academic Press.

- Graumlich, L.J. (1987). Dendrochronology: Principles and Practice. Science, 236, 1080–1081.

- Stokes, M.A., & Smiley, T.L. (1996). An Introduction to Tree-Ring Dating. University of Arizona Press.

- NOAA International Tree-Ring Data Bank: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/paleoclimatology/tree-ring

Seed Dispersal Mechanisms and Decay Adaptations

- Fenner, M., & Thompson, K. (2005). The Ecology of Seeds. Cambridge University Press.

- Dennis, A.J., Green, R.J., Schupp, E.W., & Westcott, D.A. (Eds.). (2007). Seed Dispersal: Theory and its Application in a Changing World. CABI.

- Glover, B.J. (2014). Understanding Flowers and Flowering. Oxford University Press.

- Baskin, C.C., & Baskin, J.M. (2014). Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination (2nd Edition). Academic Press.

Web and Educational Resources

- Kew Science: https://powo.science.kew.org/

- Royal Horticultural Society: https://www.rhs.org.uk/

- Missouri Botanical Garden: https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/

- Botanical Society of America: https://cms.botany.org/home/resources/botany-for-you.html

- Smithsonian Museum of Natural History: https://naturalhistory.si.edu/

- National Climatic Data Center: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data-access/paleoclimatology-data/datasets/tree-ring

Categories: : All, Cellular, plant structure

Rosalie Sinclair

Rosalie Sinclair