Hidden Sculptors: Why Plants Might Be the Best Sculptors You’ve Never Noticed

Discover how plants, as nature’s quiet artists, sculpt stunning forms, where science meets art, inspiring new ways to see the living world’s beauty.

What if some of the most inventive sculptors in the world do not work in marble or bronze at all? What if they are rooted in soil, stretching quietly toward the sky, shaping their world through living form?

All around us, plants are created with sunlight, water, chemistry, and time. Their spirals, textures, and branching patterns rival the work of any gallery artist. Unlike human creators, they ask for no spotlight. Their work simply grows and waits for someone to pause long enough to notice.

When Is a Leaf More Than a Leaf?

One day during fieldwork, I stopped at the edge of a cliff trail. The wind had carved ripples across the grasses, but my attention was caught on a single rosette of leaves. It was growing out of the rock, perfectly balanced, arranged in a spiral so precisely it looked intentional. At first, I admired its clever design as a survival strategy. But the longer I stared, the more it felt like a sculpture.

This raised a question that has stayed with me. If a structure is created by nature without conscious intent, yet still evokes awe or beauty, can it be called art?

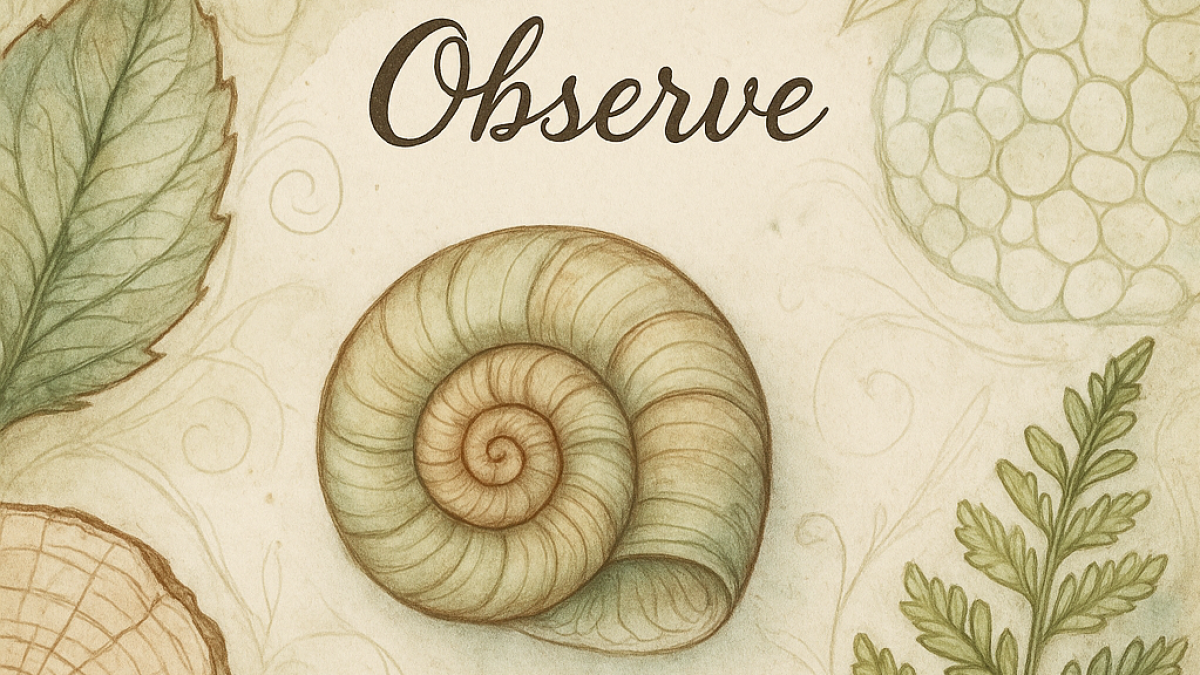

Spirals and Sunflowers: Nature’s Shared Language of Beauty

Many plants use spiral arrangements to position their leaves and seeds. This pattern, called phyllotaxis, follows the Fibonacci sequence. Each number builds on the ones before, and this mathematical rhythm allows plants to catch light efficiently without shading themselves.

Humans have used this same pattern in architecture and art for thousands of years. From the curved columns of ancient temples to Da Vinci’s sketches and Dalí’s paintings, this spiral appears again and again. It feels familiar, intuitive, and pleasing.

Have you ever looked closely at the center of a sunflower or paused to admire the curve of a pinecone in your hand? Maybe you’ve caught a spiral in the twist of a staircase or in the pattern of a mosaic beneath your feet and felt that quiet thrill of recognition. These shapes aren't just beautiful. They're everywhere, stitched into both the wildness of nature and the design of our built world.

What is it about spirals that feels so familiar, so timeless across cultures?

In a sunflower, each seed follows a precise, swirling rhythm. Pinecones, shells, and even storms follow the same path. These spirals often reflect the Fibonacci sequence, a simple mathematical rule that guides growth in efficient, elegant ways. The curve helps each seed catch light, and each scale opens just right.

Spirals also appear in the choices we make, in the structures we build. The spiral staircase isn’t only practical. It feels right. Ancient mosaics, carvings, and textiles all echo this form. Across continents and generations, we return to it. Not by accident, but by some deep knowing.

Spirals rise from soil, appear in galaxies, and unfurl in our stories. Carl Jung described them as an archetype, a symbol of transformation, cycles, and becoming.

The next time one catches your eye, take a moment. There is something in its quiet rhythm that connects us to the world and each other. Something that invites us to keep growing. If you are a reader who needs a more concrete answer: Spirals are everywhere because they are an efficient, beautiful solution in both nature and human culture, deeply tied to how things grow, move, and evolve. I invite you with this more familiar concept to explore a few other ways plants reach out as artists of their own, and show off for us, every day we can appreciate both artistically and scientifically

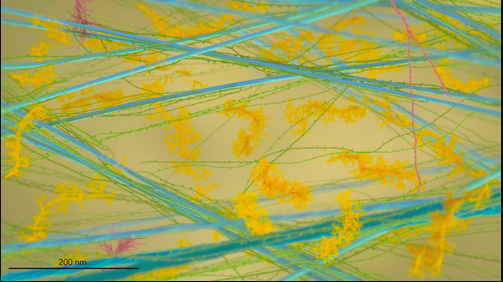

Leaf Veins and Life Maps: Seeing Beneath the Surface

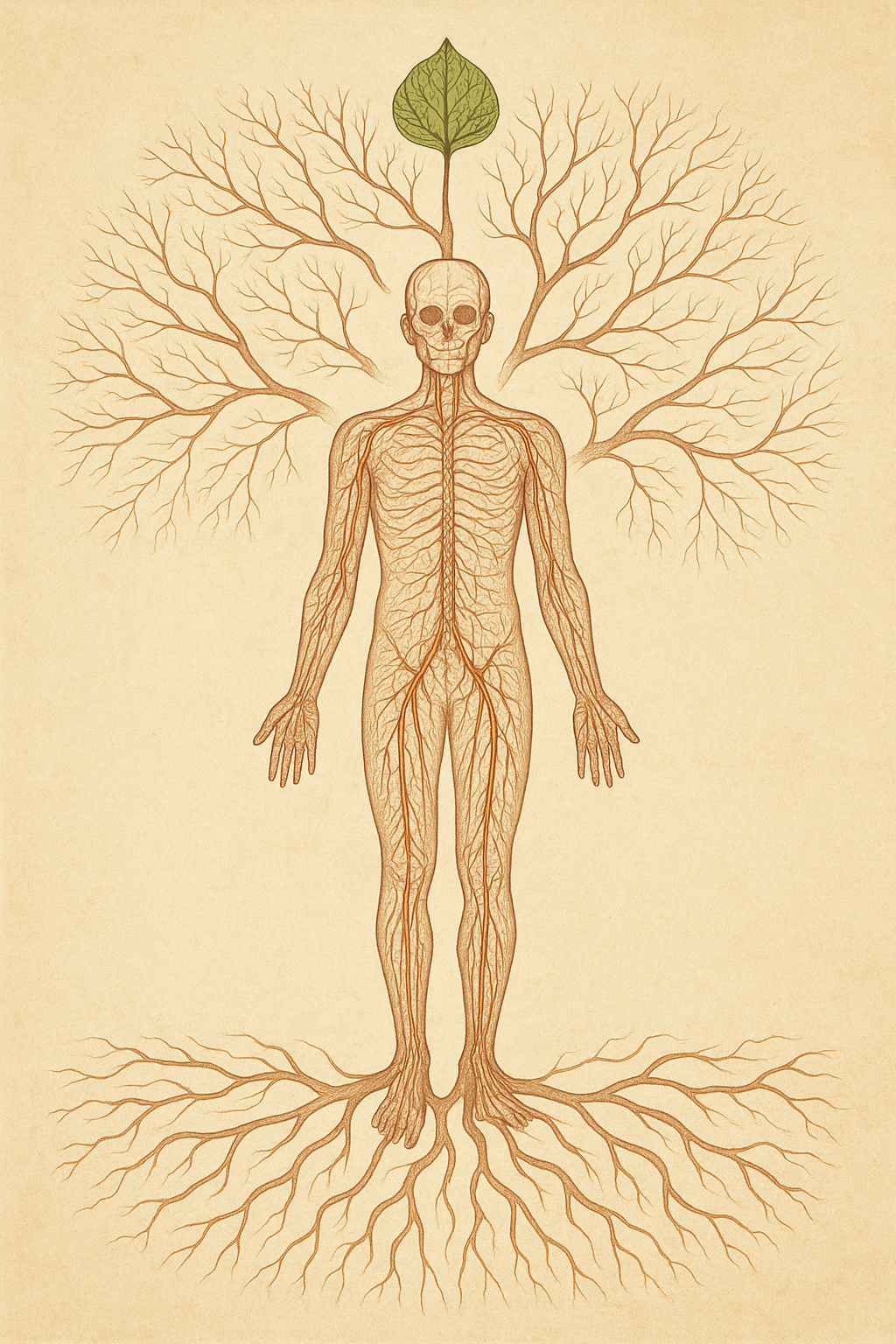

Hold a leaf to the light and you will see a branching network inside. These veins are not decorative. They carry water and sugar throughout the plant and support the leaf’s structure. Scientists call these pathways xylem and phloem.

In the lab, we use special dyes that highlight these systems in vibrant pinks and blues. Under a microscope, a stained leaf can look like a stained-glass window. Artists have long taken inspiration from these patterns. You can find echoes of them in cathedral ceilings, Art Nouveau jewelry, and the sweeping lines of ironwork gates.

Does knowing the veins serve a function change how you feel about their beauty? Or does it add to your appreciation of their design?

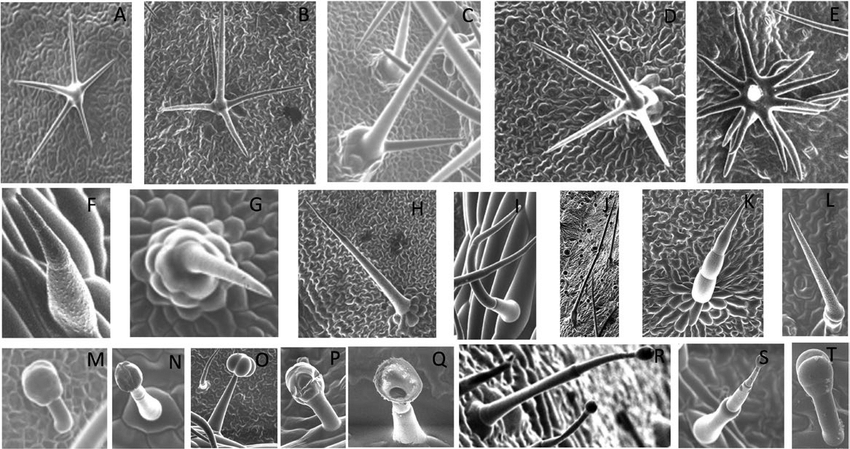

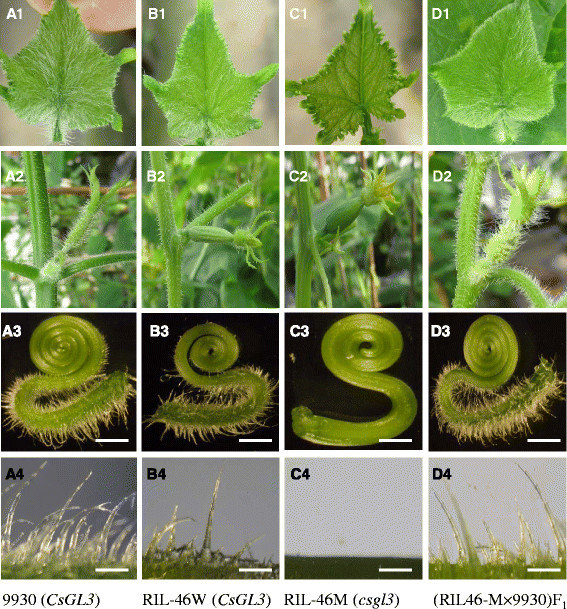

Surface and Sensation: The Sculpture of Texture

Touch a leaf and you are reading a plant’s story through texture. The soft fuzz of lamb’s ear, the waxy coat of a succulent, the tiny bristles of a tomato stem, all serve a purpose. These features protect the plant from heat, wind, and insects. All of these surfaces often come down to specialized cells called Tichomes, tiny hair-like structures on plant surfaces.

When viewed under a microscope, these structures become even more remarkable. Hairs twist into towers. Wax creates geometric ridges. They resemble the brushstrokes of a painter or the folds of fabric in a sculpture.

Have you ever found yourself drawn to a plant’s texture in the same way you are drawn to a favorite object in a museum? Does learning that these surfaces evolved for defense change your response, or deepen your curiosity?

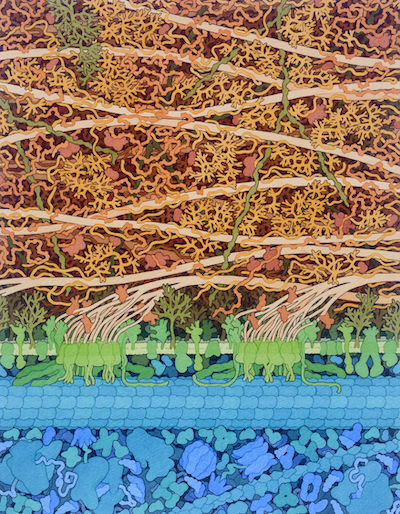

What Plants Build in Secret

Inside each plant cell, an incredible construction project is always in motion. When a cell divides, it creates a new wall from within. Tiny vesicles carry building materials to the center, where they meet and fuse into a growing plate. This plate becomes a permanent wall, made of woven cellulose, sticky pectin, and structural proteins.

With advanced imaging tools, we can now watch this process happen in real time. What was once invisible now looks like a dance. Materials stretch, shift, and snap into place with grace and purpose.

This architecture happens at the tiniest scale. Yet it inspires artists, designers, and engineers. Paul Klee once sketched abstract grids based on biological forms. The patterns he studied still unfold in every growing root and leaf.

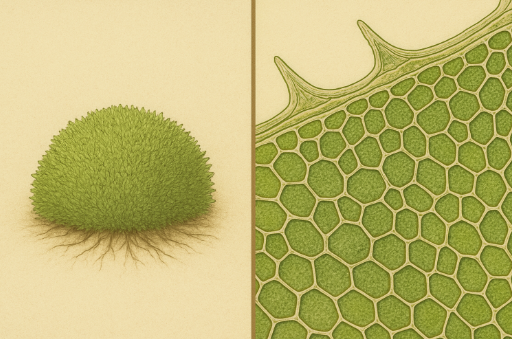

Mosses, Liverworts, and the Art of Being Small

Some of the most intricate botanical forms grow low to the ground, where few people ever look. Mosses and liverworts weave soft carpets along stones and logs. To the naked eye, they seem simple. Under magnification, they reveal a world of detailed geometry.

Liverworts, for example, have cells filled with shimmering oil bodies and reinforced corners called trigones. Their leaves overlap like scales. Their forms could inspire the design of jewelry or textiles.

One afternoon, I crouched near a boulder and spotted what looked like a patch of moss. Through a lens, it transformed. I saw tiny trees, geometric leaves, and orange capsules rising like towers. None of it had been designed for human eyes, and yet it held me there in wonder.

Why do we so often overlook what is small or hidden? What defines a masterpiece, its scale, or its impact?

Every Plant a Living Gallery

Plants build with time and necessity. They are architects shaped by light and weather. Their designs may begin with function, but again and again, they cross into the realm of the beautiful.

Next time you walk past a sidewalk crack filled with moss or a vine curling up a fence, pause. Look closer. Are you seeing only survival, or something more? Can a leaf’s curve or a seed’s spiral stir the same questions as a piece of sculpture?

Let’s Make It a Conversation

I would love to hear what moves you. Has a plant ever inspired you the way a piece of art in a museum might? Do you have a favorite leaf, bark, seed, or vine that felt like sculpture in your hands or beneath your lens?

Here are a few ways to join the conversation:

- Compare your favorite plant structures to a human-made piece of art. What do they have in common?

- Share a photo or sketch of a plant that captured your attention. What made it feel special?

- Reflect with a friend: Does knowing the function behind a plant’s form change how you see its beauty?

And if you would like a guide for your next walk, I’ve created something to help you notice and document nature’s designs. The Sketch Prompt Sheet is a free printable that invites you to observe more deeply and see more clearly, no background in science or art required.

[Download the Sketch Prompt Sheet]

Art is not always framed or named. Sometimes, it simply grows.

Meet Other Artists Who See Science as Their Studio

If you find the boundary between nature’s design and human creativity delightfully blurry, you’re in good company. Across centuries, some of the most boundary-pushing artists have also been dedicated scientists, using curiosity as both microscope and paintbrush. Here are just a few kindred spirits whose work might inspire your next nature ramble or your next sketch:

- Leonardo da Vinci, the original artist-inventor, found endless patterns in bone, leaf, and water, sketching hundreds of plant forms with almost scientific accuracy.

- Maria Sibylla Merian, an early naturalist, pioneered botanical and insect illustration so detailed that it advanced science itself.

- Anna Atkins, the first person to publish a book illustrated with photography, turned cyanotypes of algae and ferns into both scientific reference and blue-hued art.

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Nobel-winning neuroscientist, drew neurons with such beauty that his illustrations now hang in both medical texts and major art museums.

- Neri Oxman blends materials science, architecture, and biology into art installations that look as if they grew naturally, because sometimes, they do.

- Suzanne Anker sculpts with genetics, making “BioArt” that brings petri-dish discoveries into the gallery.

- Luke Jerram transforms viruses and sound waves into glass art, reimagining the invisible world as dazzling and real.

- Joe Davis codes art into the language of DNA and collaborates with molecular biologists to create living sculptures.

- Cornelia Hesse-Honegger paints mutated insects collected near nuclear sites, a project that is both citizen science and visual art.

- Natalie Jeremijenko’s work turns scientific data into participatory public art, inviting people to interact directly with the urban and natural environment.

These “artist-scientists” remind us that wonder doesn’t fit in a box, sometimes it takes form in an experiment, in a sketchbook, sometimes in the quietly perfect spiral of a leaf. Their work asks the same questions as a rosette on a cliff: Can function and beauty be the same? Can close observation be its own act of creation?

Who else belongs on your list of nature-inspired artists? Maybe you! Share what you find beautiful, curious, or inspiring, whether it started in a studio, a lab, or a patch of wild moss.

References & Further Reading

- Jean, R. V. (1994). Phyllotaxis: A Systemic Study in Plant Morphogenesis. Cambridge University Press.

(Explores the mathematics behind plant spirals and their biological significance.) - Niklas, K. J. (1992). Plant Biomechanics: An Engineering Approach to Plant Form and Function. University of Chicago Press.

(Details the engineering strategies behind plant strength and architecture.) - Taiz, L. & Zeiger, E. (2021). Plant Physiology and Development (7th Ed.). Oxford University Press.

(A comprehensive resource on plant anatomy, including vascular systems, cell walls, and protective structures.) - NASA's Earth Observatory:

River Deltas from Space

(Great visuals for understanding natural vein-like patterns at different scales.) - National Geographic:

"The Fibonacci Sequence: Why is this spiral shape so common in nature?"

(Popular science explanation of spirals in nature.) - Buchanan, B., Gruissem, W., & Jones, R. (2015). Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants (2nd Ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

(In-depth discussion of plant cell structure and wall building.) - Goffinet, B., & Shaw, A. J. (2009). Bryophyte Biology (2nd Ed.). Cambridge University Press.

(All about mosses, liverworts, and their evolutionary marvels.) - Nikam, T. D., Patil, M. V., & Chavan, S. S. (2021). Trichome diversity in Solanum species: A scanning electron microscopic study. Journal of Microscopy and Ultrastructure, 9(4), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.4103/JMAU.JMAU_43_21

- Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Song, Z., Zhang, H., Liu, Y., & Yang, M. (2015). Trichome and cuticle development in cucumber requires the tomato HD-ZIP IV transcription factor GLABRA3 homolog. Horticulture Research, 2, 15014. https://doi.org/10.1038/hortres.2015.

- Sinclair, R., Hsu, G., Davis, D., Chang, M., Rosquete, M., Iwasa, J.H. and Drakakaki, G. (2022), Plant cytokinesis and the construction of new cell wall. FEBS Lett, 596: 2243-2255. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.14426

Categories: : All, plant structure

Rosalie Sinclair

Rosalie Sinclair